In her speech at the climate negotiations in Paris this week, Australia’s Foreign Minister, Julie Bishop, tried in vain to make the case that “coal will remain critical to promoting prosperity, growing economies and alleviating hunger for years.”

Australia has been mouthing ambitious-sounding platitudes, while consistently failing to deliver policies that would actually deliver an ambitious agreement. In fact, Australia was ranked third last out of 58 countries on its climate policies.

Australia failed to support a group of countries pushing for end to fossil fuel subsidies – making a mockery of its claims even to fiscal responsibility, let alone environmental responsibility.

And Australia found itself outside the ‘High Ambition Coalition’ of more than 100 countries pushing for limiting warming to 1.5°C, which includes the EU, US, New Zealand, Canada, Africa and the Pacific island states. At the time of writing it had tried to join, but had not yet been welcomed into the group, with the convenors apparently preferring a narrower gap between rhetoric and actual policy measures.

What is behind Australia’s appalling record on climate change? When Australia is the driest inhabited continent, with ecosystems and population centres highly vulnerable to droughts, floods and bushfires, to say nothing of the threat to the Great Barrier Reef – why is Australia so blind?

One word: Coal.

The Australian Government’s Department of Industry expects (pp. 44 & 56) Australia to export 400 million tonnes (Mt) of coal this financial year. When that coal is burnt, it will release around 955 Mt CO2-equivalent.* To put that figure in perspective, Germany’s CO2 emissions in 2012 were just 817 Mt.

In July this year the US Government revised its estimates for the net present value of global damage caused by CO2 emissions. These estimates are based on very conservative Integrated Assessment Models, which, for many reasons, significantly under-estimate the costs of damage. Even so, the results are sobering – precisely because they are estimated by such conservative models, with the full backing of multiple agencies of the US Government. In short, these estimates are the least alarmist measures we have of the damage being inflicted on the world by greenhouse gas emissions.

By these US Government estimates, each metric tonne of coal burnt leads to between US$30 and US$292 damage to the world (in 2015 dollars; A$41-403). The low estimate is obtained using high discount rates (effectively valuing the future less), and the higher estimate takes somewhat better (but still inadequate) account of the likelihood of abrupt climatic changes and catastrophic damage.

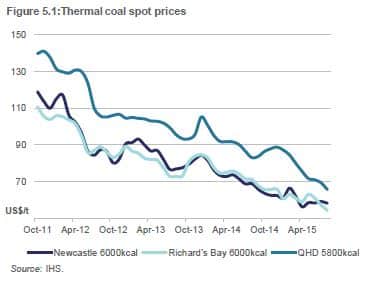

Compare these estimates for global damage with the actual price of coal:

Source: OCE, (2015) “Resources and Energy Quarterly“, Canberra, Office of the Chief Economist, Department of Industry & Science, Australian Government, September Quarter, 125 pp.

It is clear from these charts that the cost of the damage caused by burning more than a tonne of coal is now likely to be greater than the price of the coal itself.

Using the US Government damage figures, Australia’s coal exports this financial year will cause between US$12 billion and US$117 billion (A$16-161 billion) worth of damage globally.

The cost of this damage is completely ignored in the price of coal.

It may be argued that this reasoning does not take into account the potential economic benefits from the energy produced from the coal. That is true. I am also not making a distinction between thermal coal used for generating electricity (about 51% of Australia’s exports by volume) and metallurgical coal used for steelmaking (about 49%), for which alternatives are available.

The fact remains that the damages caused by the emissions from coal combustion are ignored in its price. Economists call this an externality. Coal companies externalise or dump the cost on people and the environment because they can. They pretend that coal is a cheap source of fuel and so is good for the poor. Coal isn’t cheap though – and it is a lie for politicians and the mining industry to continue to claim that it is. It only looks cheap because of the hidden subsidy it gets because its price ignores the damage its emissions cause (and we are not here, even considering the damage and health effects from the particulates and mercury caused by coal transport and combustion).

The prices of coal and other fossil fuels should be much higher to internalise the costs of the damage they cause – otherwise markets will continue to give misleading signals. The fact that free-market think tanks generally do not champion the internalisation of externalised costs shows that fundamentally they are industry shills and front groups rather than sources of informed and constructive economic policy advice.

But I digress. What is interesting is that the total revenue (pp. 44 & 56) expected from Australia’s coal exports this year is only US$27.4 billion (A$37.9 billion). That’s not profit – that’s just revenue. Since the coal industry is in dire straits globally, we can be sure that actual profits are a small fraction of revenues. That means that the unpriced damage caused by our coal exports is far greater than the profits made from those exports.

In short, Australia’s coal exports are causing massive environmental, social and economic damage which is not factored into their prices, for a profit that is far less than the costs of the damage.

And it gets worse. Australia wants to export even more coal – including a proposal to massively expand production from the Galilee Basin in Queensland, overseen by a company whose Chief Executive in Australia failed to disclose that he oversaw an appalling environmental disaster in Zambia.

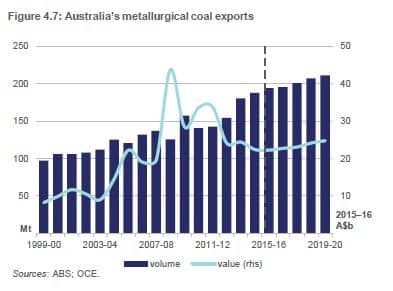

By 2020 Australian expects to be exporting 433 Mt of coal each year, which would lead to emissions of 1033 Mt and damages of between US$14 billion and US$144 billion (A$19 – 199 billion). Here are the government’s projections:

Source: OCE, (2015) “Resources and Energy Quarterly“, Canberra, Office of the Chief Economist, Department of Industry & Science, Australian Government, September Quarter, 125 pp.

This brings us to Australia’s promises to help developing countries to adapt to climate change. The rich countries have together promised US$100 billion for developing countries. Where this is all going to come from remains unclear. With much fanfare, Australia has pledged A$1 billion (US$725 million) over five years. This is not new money, but will be redirected from the existing aid budget, which the Coalition government has cut since coming to office.

Assuming the A$1 billion is spread evenly over the five years, we have A$200 million per year promised to help some of the poorest countries in the world to cope with the damage Australia is helping to cause.

That means that this year the costs of the damage from Australia’s coal exports are between 82 and 805 times what we have promised to help developing countries with. By 2020, if export expansion continues, the damage will be 97 to 993 times more. In other words: By 2020, Australia’s coal exports will be causing damage equivalent to between about 100 and 1000 times more than the amount Australia has promised to help address that damage.

It is not hard to understand why developing countries despair at Australia’s short-sighted and self-destructive duplicity.

Notes:

* With an energy content factor of about 27 GJ/tCoal, and an emissions factor (including oxidation factor) for CO2 of about 88.2 kgCO2-e/GJ, this gives 2.38 tonnes of CO2-e (CO2-equivalent) from every tonne of coal burnt. The effects of methane and nitrous oxide released from coal combustion bump it up to 2.39 tCO2-e.

** This article updates some of the information originally published in The Conversation in 2013. Read the earlier article.