Sunday, 20th October 2019

Balliol College Chapel, University of Oxford

Readings: Amos 5: 4-24; Matthew 7: 12-29

For pdf version click here.

For the audio click here or on the link below (though there is a bit of an echo)

Part of my preparation for this talk was a bit unusual – it involved binge-watching Christopher Hitchens debating various religious leaders on YouTube. Hitchens, who died in 2011, was a student at Balliol graduating in PPE in 1970. He became a famous writer and polemicist, and a fierce opponent of religions. His most famous book on that subject, from 2007, was called God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. I certainly don’t agree with all that Hitchens said, but one thing that struck me repeatedly when reading and listening to him, was his insistence on calling out what we might politely call bovine excreta: the fatuous pomposity of some clerics, the facile nonsensical arguments of others, the defenses of the indefensible in the name of religion, and his courteous but nonetheless devastating responses to his opponents. He was not in the business of playing nice. Much like Amos in the reading we heard earlier. And, ironically, much like Jesus.

In one debate Hitchens lashes his bishop opponent, saying “How can this church say it has any moral superiority? It has difficulty catching up with what ordinary people regard as common, moral and ethical sense.”

(Quote begins at 10.04)

Hitchens was in fact rather more mild than Jesus in his own excoriating attack on the religious leaders of his day. In Matthew 23:27 Jesus rebukes them saying, “For you are like whitewashed tombs, which on the outside look beautiful, but inside they are full of the bones of the dead and of all kinds of filth.”

So the first point I have learned and want to emphasise, is that the critics of religion are often right – and those of us who have a faith, need to listen more to the best critics. They are often modern examples of the ancient Hebrew prophetic tradition of speaking truth to power. And so not only are the critics often right, they were also anticipated by the Hebrew prophets and by Jesus himself!

If you have a faith, then all truth is God’s truth. Don’t be afraid then, of thoughtful critics and piercing questions, and where your search might lead. Our faith is meant to grow, and it doesn’t always grow by becoming stronger every step of the way. Sometimes long-held beliefs will be stripped away from us, like the pruning of a tree, making room for new growth. Life will occasionally throw shattering experiences at us, and our faith may crumble to dust for a time. But if God is real, and if God loves everyone, and I believe both are true, then God will help us in our honest searching.

The scriptures of the various religions were usually written to paint the rulers, and the ruling classes, in the best possible light – often giving divine sanction to the existing power structures. These ancient academics knew what their patrons wanted to hear. The Jewish scriptures were unusual though, in recording the failings of their kings, and numerous instances of prophets like Amos rebuking them. In Amos, we see the prophet open, onto the rulers of Israel, what I believe Biblical scholars today technically call “a can of whoop-ass”.

In the reading from Matthew, Jesus overturns all expectations by summing up the law and the prophets with the command to treat others as they would want to be treated; elsewhere commanding his followers to “love your enemies” (Matthew 5.44; Luke 6:27 & 35), and in the Gospel of John (John 13:34; 15:12; 15:17), summarising this simply as “love one another”. So that is the point: to love God and to love one another, to love others as we love ourselves, and to treat others as we would want to be treated. And then in the rest of the reading from Matthew, comes the kicker: “On that day many will say to me, ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many deeds of power in your name?’ Then I will declare to them, ‘I never knew you; go away from me, you evildoers.’

So Jesus is fully anticipating the hypocrisy and delusion of the kinds of religious believers that Hitchens so loathed. Notice what they focus on in their defence – “deeds of power.” Not deeds of love. Not deeds of service. They have missed the point entirely. There are two aspects to Jesus’ reply: First, that he never knew them. There was no real relationship. They weren’t doing what they were doing grounded in that relationship of love, and service, and transformation. And as a result, second, they became blinded, doers of evil, of unloving actions designed to serve their own selfish ends and their own lust for power. Jesus anticipated this.

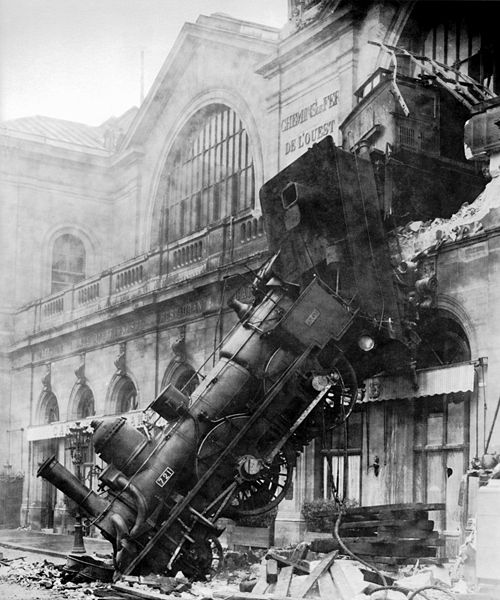

In the year 380, under the Emperor Theodosius I, Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire. In my view, this was a disaster. Wherever there is power, some people are attracted like moths to a flame. So ever since Christianity became the state religion, and probably for some time before that, we’ve had people seeking positions of power in the churches for no reason other than their love of power and control. Many were weeded out, but not enough. And so, while there were many saints and mystics and countless unsung good and faithful people, Christian history also became littered with the wreckage of broken lives from imperialism, persecution, pogroms, and institutional abuse. “‘I never knew you” Jesus says, “go away from me, you evildoers.”

The emphasis in both Amos’s and in Jesus’s words is on what we do. And that is the second point. The journey of faith is mostly about what we do, not what we think in our heads and what we say we believe. The life of faith is not primarily about intellectual assent to a set of propositions. It’s a dynamic relationship of love with the Divine that transforms us from the inside out, affecting every aspect of our lives. Jesus said in the reading “You will know them by their fruits.” The apostle James (James 2:18-19) in his New Testament letter, said “You believe that God is one; good for you. But even the demons believe that”. In other words, faith is not just intellectual agreement. James goes on: “faith apart from works is barren” (James 2:20). Or as Jesus put it in our reading today (Matthew 7:12) “In everything do to others as you would have them do to you; for this is the law and the prophets.”

At the World Economic Forum in January this year, the young Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg delivered a stark message: “Adults keep saying: ‘We owe it to the young people to give them hope.’ But I don’t want your hope. I don’t want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. And then I want you to act. I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if our house is on fire. Because it is.”

At the UN in New York in September Greta delivered another scathing speech saying, “You say you hear us and that you understand the urgency. But no matter how sad and angry I am, I do not want to believe that. Because if you really understood the situation and still kept on failing to act, then you would be evil. And that I refuse to believe.”

Again – it is actions that matter. Not words. Just like in Amos. Just like Jesus said in Matthew.

I’ve found it intriguing that the term ‘social justice warrior’ has become a term of mockery and derision in some circles. Or the word ‘Snowflake’. The comedian John Cleese famously tweeted last year: “Yes I’ve heard this word. I think sociopaths use it in an attempt to discredit the notion of empathy” (8 July 2018)

Cleese makes an important, and profoundly biblical link here. And this is the third point I want to emphasise: that concern for justice is rooted in empathy, and sustained by love. And conversely, lack of concern for social injustice, is rooted in a failure to love.

‘Sin’ is an immensely powerful and important idea that has been distorted and trivialised. It essentially means ‘missing the mark’ – like a drunken archer. It’s been mocked and caricatured – often deservedly so, with the church’s obsession with bodily functions. But, you know, once you’re the state religion under the patronage and protection of the empire, you can’t go about challenging the imperial structures of abuse, extraction and oppression – so you have to shift your focus to something more manageable and more private, like what people do between the sheets, and controlling women’s bodies.

In essence though, ‘sin’ means acting without love – using and abusing other people, animals and the natural world as instruments for our own selfish ends. It’s that seeing others as a means to an end – a means merely to our own satisfaction – that is the essence of sin. Using others when they should be treated with love and respect and concern for their highest wellbeing. Acting without their consent. Rejecting the bond of shared humanity. Ignoring the suffering of those who can’t do anything for us. Rejecting our connection to the animals and our duty to care for them.

Christopher Hitchens and Greta Thunberg, in their different ways, both display a fierce, prophetic, fiery denunciation of sin – though neither of them would likely call it that.

Hitchens railed against the hypocrisy of the church, the protection of abusers, the alleged war crimes of a certain US Secretary of State, and the cowardice of the West that allowed 8,000 mainly Muslim men and boys to be slaughtered in Srebrenica during the Balkan wars in 1995.

More recently, Greta Thunburg thundered against the world’s disinterested leaders, wallowing lazily in denial: “You are failing us.” she said, “But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say we will never forgive you. We will not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the line. The world is waking up. And change is coming, whether you like it or not.”

Exactly like Amos. Enough with the insipid platitudes. Through Amos, God said, “I hate, I despise your festivals. … But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.!” (Amos 5: 21 & 24).

So it is action that matters – action rooted in and flowing from love. And love for ourselves, for other people, for all sentient beings and for the planet we live on, implies a resistance towards all that is dehumanising, oppressive, unjust, and degrading – a resistance toward all that flows from a lack of love, or what we call ‘evil’.

In 1867 the British philosopher and political theorist John Stuart Mill said “Let not any one pacify [their] conscience by the delusion that [they] can do no harm if [they] take no part, and form no opinion. Bad [people] need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good [people] should look on and do nothing.”

So these are not simply individualistic teachings. This is not merely about our personal private spirituality. It is about our shared humanity and our love for our fellow beings – and about the systems and structures that perpetuate abuses of power. The reading from Matthew said that Jesus inspired the crowds, who were astounded at his teaching. Why? Because, “he taught them as one having authority, and not as their scribes.”

Jesus upturned their expectations, and blew apart their pre-conceived ideas of who God was, and who they were before God. He taught with authority. Reminding people that the scriptures and the traditions were meant to serve the people – especially the poor, the outcast, the sick, the powerless. Not the powerful, who hoarded their wealth and abused the poor. Not the pompous, with their elaborate ceremonies and festivals. In the context of a just society, and of love and concern for our fellow beings, for the powerless and the oppressed, then sure, festivals and ceremonies can be a beautiful celebration of that. But without justice; without ‘righteousness’ – things being made right; in a world groaning under oppressive, deceitful, inept, and corrupt rulers, then Amos says, their feasts and fatuous, self-congratulatory celebrations are an abomination to God. The image he uses is like a dam bursting upon them.

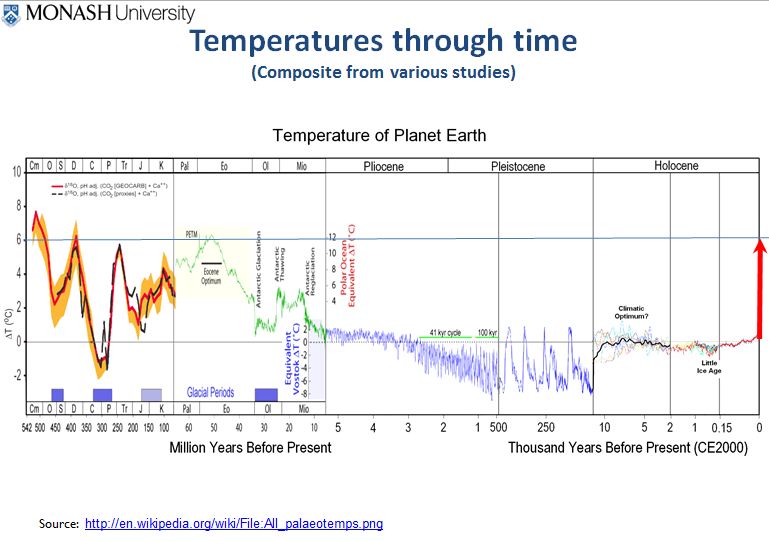

We who are here at Oxford now, are here at a time of immense global challenges as we humans abuse the freedom we have been given, acting in unloving and indifferent ways towards the poor and our planet. In my view, climate change is the biggest challenge. Not because we are feeling the full effects now. But because there is inertia in the system – a time lag – and so the window of opportunity to rein it in is now. But there are other issues too – like the massive inequality that sees the wealthiest 10% reap almost all of the gains since the financial crises, while the rest of the country has suffered under brutal austerity policies and public service cuts. And like the often brutal treatment of women, of people with disabilities, of people of colour, and of LGBTQI+ people all over the world.

So we have a choice as students, as visitors, and as faculty, how we respond to all this. Through it all, God is with us. Calling, drawing, seducing even. In the Islamic mystical tradition of the Sufis they speak about the fanā’ – the annihilation – the idea that we need to die before we die. It’s exactly analogous to the idea of Christian baptism – dying to our false selves and rising united with Christ, allowing ourselves to be transformed through that mystical union. It’s the annihilation of our false ego, the annihilation of our intellectual concepts about what God and life should be like, stripping us back to raw, honest, humble, being, ready to be embraced by the intoxicating, joyful, love of the Divine – that love which is the essence, the vehicle, and the goal of the journey.

I will finish with one of my favourite poems by the Sufi master Mewlānā Jalāl ad-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī – better known as Rumi, who lived in the 1200s and who taught in Konya in what is now Turkey. Towards the end of the poem Rumi invokes Shams of Tabriz, who was his teacher and who represented for Rumi the love of God. I love this poem because it captures the idea that real clarity of direction and action in a suffering world comes most fully after allowing ourselves to be swept away and transformed by the intoxicating love of God. It is that Divine, healing, transformative love, that sustains us, carries us and enables us to love others. This translation is by Andrew Harvey, who was once a fellow at All-Souls:

The whole world could be choked with thorns:

A lover’s heart will stay a rose garden.

The wheel of heaven could wind to a halt:

The world of lovers will go on turning.

Even if every being grew sad, a lover’s soul

Will stay fresh, vibrant, light.

Are all the candles out? Hand them to a lover –

A lover shoots out a hundred thousand fires.

A lover may be solitary, but he is never alone.

For companion he has always the hidden Beloved.

The drunkenness of lovers comes from the soul,

And Love’s companion stays hidden in secret.

Love cannot be deceived by a hundred promises:

It knows how innumerable the ploys of seducers are.

Wherever you find a Lover on a bed of pain –

You find the Beloved right by his bedside.

Mount the stallion of Love and do not fear the path –

Love’s stallion knows the way exactly.

With one leap, Love’s horse will carry you home

However black with obstacles the way may be.

The soul of a real lover spurns all animal fodder,

Only in the wine of bliss can his soul find peace.

Through the Grace of Shams-ud-Din of Tabriz, you will possess

A heart at once drunk and supremely lucid.

Jalal-ud-Din Rumi (1207 – 1273), as translated by Andrew Harvey (Ed.) (1997) The Essential Mystics: Selections from the World’s Great Wisdom Traditions, HarperCollins, New York, p. 159.

Thank you.