This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.

In the coming months our new federal government will be promoting a massive expansion in Australia’s coal exports. In all likelihood they’ll hail it as “good For Australia”. It isn’t.

Most of us are familiar with the damage coal mining, export and burning does to the environment. We know it affects health, contributes to climate change, risks groundwater supplies and threatens the Great Barrier Reef.

For many, that damage is offset by what they see as social and economic benefits, here and abroad. But in almost all cases, those benefits are exaggerated or non-existent.

How much carbon dioxide are we exporting?

The Australian Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics expects (p. 106) that Australia’s black coal exports in the financial year 2013-14 will be 350 million tonnes (Mt).

With an energy content factor of about 27 GJ/tCoal, and an emissions factor (including oxidation factor) for CO2 of about 88.2 kgCO2-e/GJ, this gives 2.38 tonnes of CO2-e (CO2-equivalent) from every tonne of coal burnt.

The effects of methane and nitrous oxide released from coal combustion bump it up to 2.39 tCO2-e. That implies that the combustion of our coal exports will release around 836 Mt CO2-e. To put that figure in perspective, Germany’s CO2emissions in 2011 were just 807 Mt.

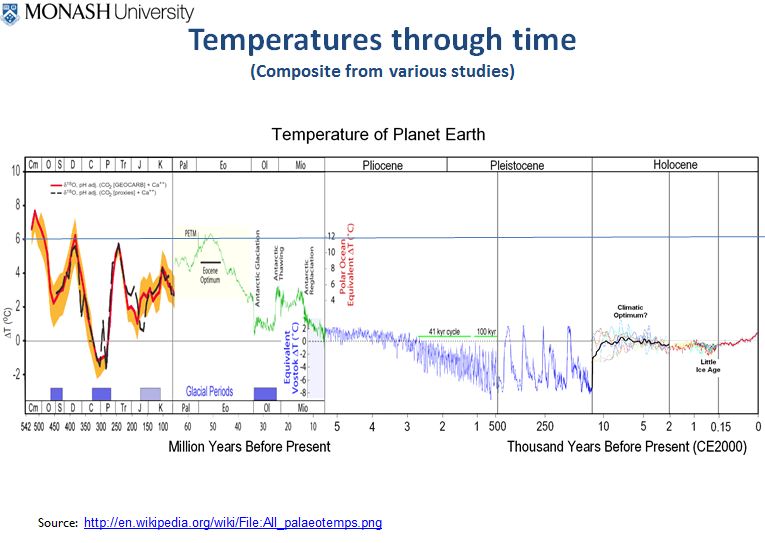

Greenpeace estimates the mega-mines planned for Queensland’s Galilee Basin alone would produce some 705 million tonnes of CO2 each year. That’s enough to chew through around 6% of the CO2 the entire world can release to keep warming to 2C above pre-industrial temperatures.

Burning coal causes billions of dollars in damage

Our coal exports are causing massive environmental, social and economic damage. These costs are not factored into coal’s export price.

In May the US Government revised its estimates for the net present value of global damage caused by CO2 emissions. These models may significantly under-estimate the costs of damage, but the results are sobering.

By these conservative US Government estimates, our current coal exports are causing between A$11 billion and A$103 billion of damage globally each year (in 2013 dollars). None of this is included in the coal export price.

When we consider that total revenues from exports in FY2013-14 (p. 94) are expected to be around A$41.5 billion, and actual profits are a much smaller fraction of revenues, we can be confident that the unpriced damage caused by our coal exports is likely to be significantly greater than the profits made from those exports.

If our coal exports were to reach 1000 Mt by 2020, they would be producing around 2390 Mt of CO2 and up to A$370 billion in global damage each year.

Pricing this damage could fund the repair

It will be argued of course, that this reasoning doesn’t take into account the economic benefits from the energy produced from the coal. True. But the export price should be higher to internalise the costs of damage – otherwise markets will continue to give misleading signals.

Correcting the market failure of externalised costs could be done either in Australia with an export tax, or in the importing countries with an import tariff or domestic price on carbon.

If Australia imposed an export tax itself, as Peter Christoff suggested, then the Australian people would capture the benefits of that revenue stream. We could fund climate adaptation measures, clean energy and disaster risk reduction in Australia. We could pay our international climate finance obligations to the poorest developing countries to help them to adapt to climate change.

The coal boom damages our economy

Treasury officials and researchers such as Richard Denniss and Matt Grudnoff have shown the resources boom helped to push up our exchange rate.

This caused significant damage to tourism, tertiary education, manufacturing, agriculture and other clean export industries – a classic example of the so-called Dutch-disease. These industries employ vastly more people (Table 06) in far more widely dispersed locations than coal mining.

Leisure tourism has also been hard hit, not only by the higher exchange rate, but by higher labour costs and difficulties attracting skilled staff.

A massive expansion of coal mining would make capital and labour even more expensive for other industries – exacerbating the crowding out effects already seen in the first phase of the mining boom.

Australia Institute researcher Mark Ogge has said: “Consultants for Clive Palmer’s China First coal mine in the Galilee basin estimated, in the company’s EIS, that this effect of driving up labor costs would mean 3,000 jobs will be lost in other parts of the economy, with manufacturing being the hardest hit.”

Powerful coal interests distort our political system

Guy Pearse and Clive Hamilton blew the whistle on the influence the fossil fuel industry has on Australia’s climate change and energy policies. Powerful coal mining companies and their lobbyists distort our political economy, and the expansion of the industry will only make the problem worse.

The tourism and education sectors are together just as significant export earners for Australia, and employ far more people, than coal mining.

But there is no equivalent to the giant mining companies in those sectors to make large political donations, or to fund well-orchestrated lobbying and media campaigns promoting their interests.

Our coal undercuts clean energy in developing countries

The argument is often made that if we really cared about the poor we’d export a lot more coal – but this is purest nonsense. It ignores the devastating costs of climate change and respiratory illnesses to the poor, and makes it harder for developing countries to transition to a clean energy future.

Wind energy is already competitive with new coal-fired power stations in India and solar is expected to be competitive by 2018.

The World Bank no longer funds coal fired power stations in developing countries and analysts at Goldman Sachs are already warning that coal export terminals are a bad investment because expected global demand for thermal coal has been over-estimated.

Australia should halt its plans to expand its coal production and exports – it enriches a few at the expense of millions and will inflict immense damage both on our own country and on the rest of the world.